Learn & thrive

The Benefits of Chewing (Backed by Research)

The Lost Art of Chewing

Once upon a time, our ancestors hunted, gathered, and consumed nutrient-dense food that was rich in fibre and protein; meats, nuts, and seeds that required serious chewing.

The Agricultural Revolution introduced carbohydrate-heavy meals but the Industrial Revolution took things further, filling our plates with ultra-processed foods that didn’t require much chewing at all.

This dietary evolution caused not only sub-optimal nutrition but a dramatic reduction in chewing, which has led to a cascade of health challenges we’re only just beginning to understand.

These problems are impacting orofacial development

Shrinking jaws

Harvard anthropologists Zink and Lieberman suggest that eating softer, processed foods has led to a de-evolution of the jaws and teeth. This notion has been supported in a global study by the University of Kent, which found that a decrease in chewing affected the way the mandible (the lower jaw) grows, in turn leading to an increased prevalence of common orthodontic problems.

Dysfunctional breathing

Up to 56% of children are mouth breathers. Mouth breathing negatively affects respiratory, cardiovascular, hematopoietic, endocrine, and dental health. It also plays a role in sleep disorders, fatigue, and developmental delays.

Decline in breastfeeding

The 2020–21 Australian National Health Survey shows that less than 3% of Australian infants are exclusively breastfed for six months and then continue breastfeeding up to 12 months. Globally, similar trends are emerging.

Breastfeeding promotes jaw development and alignment and healthy airway growth while minimising the tendency for mouth breathing.

Poor Orofacial Development can Set the Stage for:

Oral dysfunctions

- Malocclusion

- Gum & teeth disease

- Bruxism

- Jaw pain / TMJ Dysfunction

Sleep disorders

- Upper-Airway Resistance Syndrome (UARS)

- Snoring

- Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA)

Other health conditions

- Trouble chewing or swallowing

- Otitis Media

- Cognitive & behavioural issues

- Elevated stress levels

The known benefits of chewing

Chewing isn’t just about breaking down food. It’s a vital, often-overlooked functional milestone that influences jaw development, breathing, digestion, and even cognitive function.

Saliva production

Chewing can increase saliva flow by as much as 10–12 times the unstimulated rate. Saliva plays a key role in oral health, pH balance, and nutrient absorption, making it critical for proper digestion.

Jawbone strength

Consistent chewing improves jawbone density and muscle strength, supporting proper teeth alignment and facial structure. Balanced muscle strength also enhances swallowing, airway function, and maxillofacial development (facial growth).

Nasal breathing

Correct chewing supports lip and tongue posture and function, which are essential for nasal breathing. Nasal breathing is linked to better sleep, improved oxygen absorption, and reduced daytime fatigue.

Chewing properly also helps keep your nasal passages clear by encouraging co-ordinated Chew- swallow- breathe synchrony.

Feeding function

We need to chew properly to create the soft bolus (chewed food) essential for healthy feeding. Chewing strengthens tongue and cheek muscles, which helps improve swallowing and reduce issues like choking and excessive drooling.

Other Possible Benefits to Chew Over

The science is still catching up to what our ancestors knew instinctively: there is so much good a chew can do for you. While some benefits of chewing are well and truly confirmed, we’re just starting to learn more about its impact on other areas of health and development.

Cognitive function

Chewing has been shown to enhance focus, boost mood, and relieve stress. It also likely plays a key neurodevelopmental role in helping infants learn to coordinate the chew-swallow-breathe sequence, a developmental progression from the suck-swallow-breathe sequence essential for survival.

TMJ stability

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) that connects your lower jaw to your skull relies on well-conditioned chewing muscles (masseters and temporalis). Poor chewing habits can lead to jaw pain, tension headaches, and TMJ dysfunction.

Inner ear health

A good chew helps you swallow more efficiently and activates the muscles around the ears, allowing your auditory tubes to open more often. This improves middle-ear ventilation, keeping your ears clear of stagnation and reducing the risk of infections.

Gag reflex

Regular chewing and swallowing are believed to help train a healthy gag reflex. Chewing also provides consistent sensory input, which may help reduce sensitivity and integrate an overactive gag reflex.

Myo Munchee: The chew that’s good for you

It may be simple but chewing well could be one of the most profound health habits you can adopt.

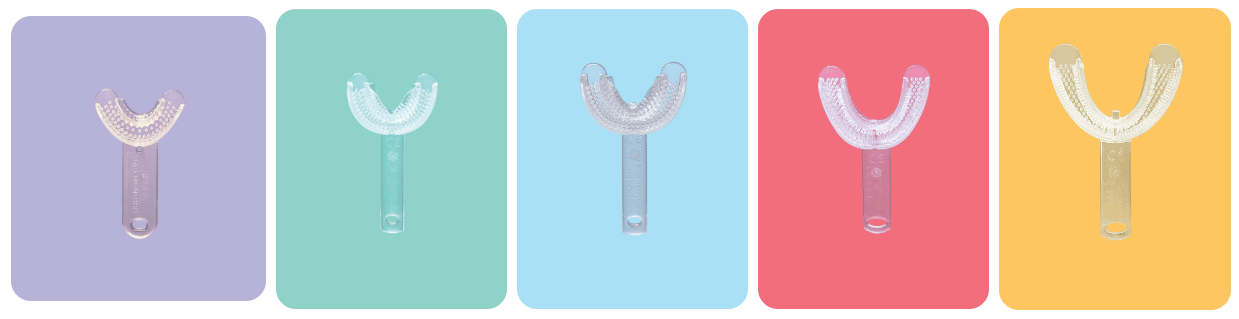

The Myo Munchee is a small chewing device designed to restore the lost art of chewing. By facilitating safe and effective chewing, it helps support jaw health, airway development, and overall wellbeing.

References

1. Wang, L. et al. (2021) ‘Trends in consumption of ultraprocessed foods among US youths aged 2-19 years, 1999-2018’, JAMA, 326(6), p. 519. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.10238.

2. Zink, K.D. and Lieberman D.E. (2016) ‘Impact of meat and Lower Palaeolithic food processing techniques on chewing in humans’, Nature, 531(7595). 10.1038/nature16990.

3. Australian Institute for Health & Welfare (2023) Australia’s mothers and babies: Breastfeeding, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers-babies/breastfeeding-practices.

4. Santacruz, C. et al. (2023) ‘Efficacy of breastfeeding in dentomaxillofacial development: Narrative review of the literature’, World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 19(1), pp. 446–454. doi:10.30574/wjarr.2023.19.1.1351.

5. Wallenborn, J.T. et al. (2021) ‘Breastfeeding, physical growth, and cognitive development’, Pediatrics, 147(5). doi:10.1542/peds.2020-008029.

6. Savian, C.M. et al. (2021) ‘Do breastfed children have a lower chance of developing mouth breathing? A systematic review and meta-analysis’, Clinical Oral Investigations, 25(4), pp. 1641–1654. doi:10.1007/s00784-021-03791-1.

7. Lin, L. et al. (2022) ‘The impact of mouth breathing on dentofacial development: A concise review’, Frontiers in Public Health, 10. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.929165.

8. Pedersen, A. et al. (2018) ‘Salivary functions in mastication, taste and textural perception, swallowing and initial digestion’, Oral Diseases, 24(8), pp. 1399–1416. doi:10.1111/odi.12867.

9. Edgar, W.M., Dawes, C. and O’Mullane, D.M. (2012) Saliva and oral health: An essential overview for the Health Professional. Duns Tew: Stephen Hancocks Limited.

10. Polland, K.E., Higgins, F. and Orchardson, R. (2003) ‘Salivary flow rate and ph during prolonged gum chewing in humans’, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 30(9), pp. 861–865. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2842.2003.01177.x.

11. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2023) Healthy mouths, healthy lives – Australia’s National Oral Health Plan 2015–2024, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/healthy-mouths-healthy-lives-australias-national-oral-health-plan2015-2024?language=en.

12. Inoue, M. et al. (2019) ‘Forceful mastication activates osteocytes and builds a stout jawbone’, Scientific Reports, 9(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-01940463-3.continued (2/3) ...

13. Mavropoulos, A. et al. (2010) ‘Rehabilitation of masticatory function improves the alveolar bone architecture of the mandible in adult rats’, Bone, 47(3), pp. 687–692. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.025.

14. Shirai, M. et al. (2018) ‘Effects of gum chewing exercise on maximum bite force according to facial morphology’, Clinical and Experimental Dental Research, 4(2), pp. 48–51. doi:10.1002/cre2.102.

15. Ingervall, B. and Bitsanis, E. (1987) ‘A pilot study of the effect of masticatory muscle training on facial growth in long-face children’, The European Journal of Orthodontics, 9(1), pp. 15–23. doi:10.1093/ejo/9.1.15.

16. Bodic, F. et al. (2005) ‘Bone loss and teeth’, Joint Bone Spine, 72(3), pp. 215–221. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2004.03.007.

17 Takahashi, M. and Satoh, Y. (2019) ‘Effects of gum chewing training on oral function in normal adults: Part 1 investigation of Perioral Muscle Pressure’, Journal of Dental Sciences, 14(1), pp. 38–46. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2018.11.002.

18. Kugimiya, Y. et al. (2021) ‘Distribution of lip‐seal strength and its relation to oral motor functions’, Clinical and Experimental Dental Research, 7(6), pp. 1122–1130. doi:10.1002/cre2.440.

19. Ingervall, B. (1978) ‘Activity of temporal and lip muscles during swallowing and chewing’, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 5(4), pp. 329–337. doi:10.1111/j.13652842.1978.tb01251.x.

20. Taner, T. and Saglam-Aydinatay, B. (2023) ‘Physiologic and dentofacial effects of mouth breathing compared to nasal breathing’, Nasal Physiology and Pathophysiology of Nasal Disorders, pp. 559–580. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-12386-3_39.

21. Matsuo, K. and Palmer, J.B. (2009) ‘Coordination of mastication, swallowing and breathing’, Japanese Dental Science Review, 45(1), pp. 31–40. doi:10.1016/j.jdsr.2009.03.004.

22. Kumar, A. et al. (2022) ‘Chewing and its influence on swallowing, gastrointestinal and nutrition-related factors: A systematic review’, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 63(33), pp. 11987–12017. doi:10.1080/10408398.2022.2098245.

23. Hirano, Y. and Onozuka, M. (2015) ‘Chewing and attention: A positive effect on sustained attention’, BioMed Research International, 2015, pp. 1–6. doi:10.1155/2015/367026.

24. Hirano, Y. and Onozuka, M. (2014) ‘Chewing and cognitive function’, Brain Nerve, 2014, 66(1), 25–32. doi:10.11477/mf.1416101690.

25. Kubo, K., Iinuma, M. and Chen, H. (2015) ‘Mastication as a stress-coping behavior’, BioMed Research International, 2015, pp. 1–11. doi:10.1155/2015/876409.continued (3/3) ...

26. De Felício, C.M. et al. (2012) ‘Electromyographic indices, orofacial myofunctional status and temporomandibular disorders severity: A correlation study’, Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 22(2), pp. 266–272. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.11.013.

27. Tartaglia, G.M. et al. (2011) ‘Surface electromyographic assessment of patients with long lasting temporomandibular joint disorder pain’, Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 21(4), pp. 659–664. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2011.03.003.

28. Kouwen, H.B. and DeJonckere, P.H. (2007) ‘Prevalence of ome is reduced in young children using chewing gum’, Ear & Hearing, 28(4), pp. 451–455. doi:10.1097/aud.0b013e31806dc1bd.

29. Passàli, D. et al. (2004) ‘Eustachian tube and otitis media’, Hearing Impairment, pp. 245–249. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-68397-1_47.

30. M Lone, I. et al. (2024) ‘Global map of skeletal and dental malocclusion prevalence: From classes to continents’, Journal of Dentistry & Oral Disorders, 10(1). doi:10.26420/jdentoraldisord.2024.1183.

31. Cramon-Taubadel, N. von (2011) ‘Global human mandibular variation reflects differences in agricultural and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(49), pp.19546–19551. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113050108.

32. Menezes, M.P. et al. (2023) ‘Bucco-maxillo and systemic repercussions of the mouth breathing syndrome: a comprehensive review', MedNEXT Journal of Medical and Health Sciences, 4. doi:10.54448/mdnt23S209.

33. Miles, T.S. (2007) 'Postural control of the human mandible’, Arch Oral Biol, 52(4), pp. 347-352. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.12.017.

34. Campbell, S.K. (1981) ‘Neural Control of Oral Somatic Motor Function’, American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 61(1), pp. 16-22. doi:10.1093/ptj/61.1.16.

35. Wilson, E. et al. (2021) 'Paediatric oral sensorimotor interventions for chewing dysfunction: A scoping review’, International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56(6), pp. 1316-1333. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12662

36. Scarborough D.R. and Isaacson L.G. (2006) ‘Hypothetical anatomical model to describe the aberrant gag reflex observed in a clinical population of orally deprived children’ Clin Anat, 19(7), pp. 640-644. doi:10.1002/ca.20301.